All parents have strong biases when it comes to managing their kids’ screen use. What are yours?

“My child would never send a nude photo, that is not how she was raised.”

“I don’t believe my child is lying to me; I have good kids.”

“Video games aren’t that bad. I played as a kid and read that video games are good for hand-eye coordination.”

“I keep an eye on what my kids do online.”

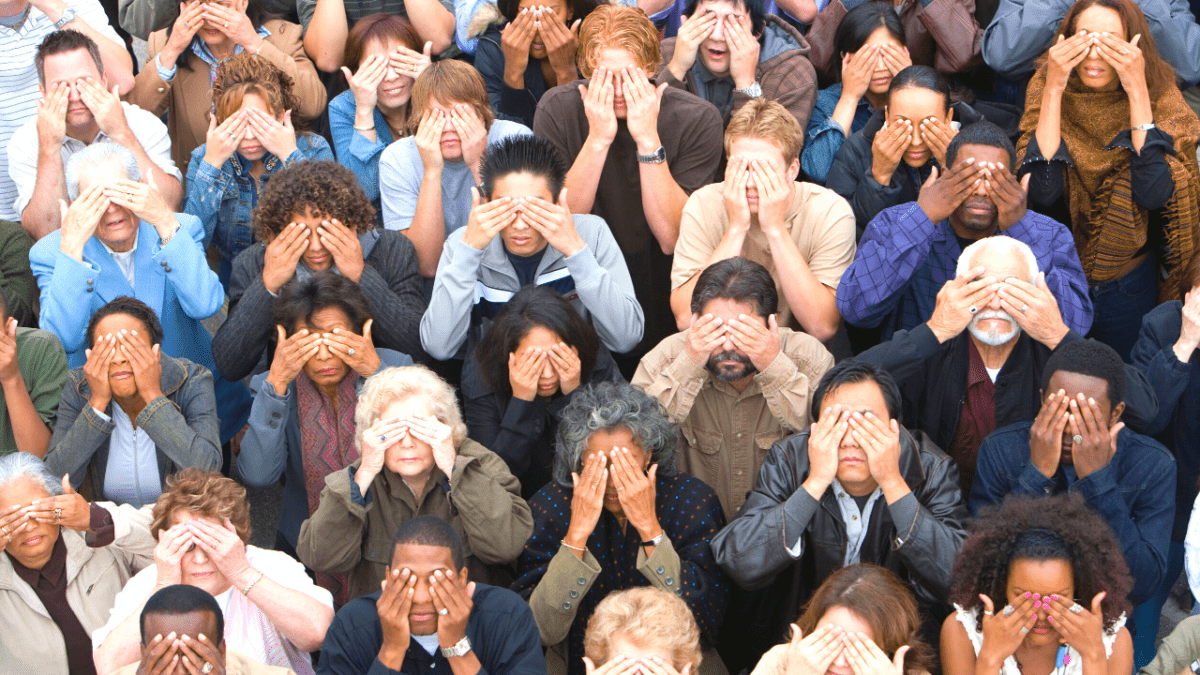

Parents love their kids and all parents have blind spots when it comes to parenting. Biases are a part of life.

Most of us can recall the fairytale of The Emperor’s New Clothes. Charlatans come to town and convince the Emperor to purchase the most magnificent clothes—clothes invisible to the stupid or incompetent. The Emperor, unable to see the clothes but too proud to admit it, struts through the town naked and everyone goes along with the ruse. It’s not until a young child, his voice ringing above the crowd, declares, “But he hasn’t got anything on!” that the townspeople finally take notice. Their pre-set bias got in the way and blinded them—the crowd wanted so badly to believe that something was true that they did.

In loving their kids, parents can likewise develop blind spots that harm rather than help. These are some early pitfalls when it comes to parenting around screens:

- Confusing physical maturity and intelligence with emotional maturity

- Believing that love always equals trust

- Relying too much on parental controls to prevent problems

- Depending only on conversations to change behavior

- Believing common screen myths and seeking to confirm personal biases

Raising kids on screens is no fairytale and ScreenStrong is here to remind everyone: the emperor isn’t wearing any clothes.

What are biases?

Biases are necessary in life. They are good to have as they help with our built-in survival skills and save energy. Our executive brain develops certain biases naturally in order to efficiently manage risks and make decisions. We depend on biases to shortcut that process. But these shortcuts can feed assumptions that blind us to early warning signs of potentially dangerous activities.

Here are a few biases that can catch parents off-guard in the screen world.

The ‘Not My Kid’ Bias, or ‘My Kid Would Never…’

“My son is not like his friends. He is mature beyond his years, an old soul, and has really good self-control.”

“My teen daughter is so smart. She is even more mature than her older brother. She is capable of navigating smartphone distractions. I don’t worry about her at all.”

Truth: It is normal for parents to think that their children are unique. Most of us see our own kids as standing out from the crowd and being more mature than they are truly capable of being. We equate certain mature actions with thinking our kids are wise. But these glimpses of maturity do not signify that our kids’ are more mature than their peers.

Looking at developmental brain science, we learn that all kids and teenagers are immature. We also learn that even our pristine parenting skills can’t speed up or force the maturity process. Maturing takes time and is not complete until we reach our mid-twenties when the frontal cortex has stronger neuronal connections. Your child may be very intelligent, but he or she is not mature. Your child is not immune to making poor judgements when it comes to using adult technologies. We hurt our kids when we believe they are immune to making bad decisions.

Parental Optimism Bias: The power of positive thinking doesn’t apply to screen use.

“I believe in my child. I want the best for her, so I trust her.”

“My child has never lied to me and I know nothing bad will happen to her online. If it does, she will tell me and we’ll handle it together.”

Truth: It is easier to overestimate the possibility of good things happening and underestimate the possibility of bad things happening than vice versa. We assume that our son will never look at pornography and that our daughter will never sext, but statistics point to a very different story. These types of activities have risen since the advent of the smartphone, despite our optimistic bias. It’s good to have a positive attitude, but this can cause parents to place too much trust in their teens. The decline in teens’ emotional health is in part a result of this bias.

The Conversation Bias: Conversations are the golden ticket to screen success.

“As long as I tell my kids not to click on certain things, not to give out personal info online, to look away when it comes to porn and violent content, and discuss other directives, they will be fine.”

“My kids will tell me if anything is wrong online.”

Truth: If conversations really worked, we would be able to eliminate teen delinquency (i.e. drug and alcohol use and teen pregnancy) simply by having conversations about it. Conversations are building blocks for a good relationship with your child, but conversations alone do not change behavior. When we depend on conversations about digital safety, we are hurting our kids. Ongoing conversations help establish you as the expert and the go-to person for life advice.

Anchoring Bias: The first thing you hear sticks.

“I trust my child on her screen. When she was only 8 she told me about something bad she saw on her iPad and showed me. I am so proud of her because she is so mature. We have a close relationship and I have no reason to believe that she will not keep being open and honest with me.”

“My kids have been watching cartoons on Youtube for years, and they’re fine.”

Truth: The anchoring bias says that we are strongly influenced by the first impression we have about a topic or person. But this first impression can incorrectly influence our judgment for future assessments. Just because your child seemed mature for her age in first grade doesn’t mean she will be mature in seventh grade. In the same vein, her telling you something once does not mean she will tell you everything.

When we have an anchoring bias, we are not open to hearing new information. We tend to get stuck referring back to a single positive incident rather than assessing our kids at their different developmental stages. What an eight-year-old does could be very different from what they do at age 12. Being open minded to new facts and ideas will help us hold our ground with screen decisions.

Confirmation Bias: Seeking out and listening only to others who believe the same way you do.

“Video games and social media are okay for my kids because contemporary culture, the education system, and all my friends believe that they are fine. Plus, we have no choice! We don’t want our kids to get left behind in learning how to use modern technology.”

“Every kid in their class has a smartphone, and they seem to be okay. I don’t want my kids to be left out socially.”

Truth: We typically seek out and read the information that confirms what we already believe. If we want to believe that social media and gaming is good for our kids, there are plenty of platforms that we can seek out to support that bias. We do this in part because it takes less energy to follow the crowd, and because we want our kids to love us, so we allow them to do everything their peers are doing. But going with the crowd is oftentimes a mistake—the crowd will take the low-effort, easy way out. Our culture will also lean toward the most financially profitable path, not the path that is best for our kids.

It takes much more energy to step away from the crowd, study the facts, and swim upstream against the predominant culture. But before you pick a crowd to join, always do your due diligence and research first. If you have a gut feeling that your child is being harmed by his screen use, step away and do your own fact-finding. It just may save your kids. Remember, you care more about your kids than the crowd does. When we refuse to look at other options we may hurt our kids.

Status Quo Bias: Change is much harder than stagnation.

“My teen already has a phone, I can’t take it away now.”

“My son has been gaming for years, he’ll lose it if I take his system away.”

We are all creatures of habit and habits are hard to break because it takes a lot of energy and effort—we lean towards keeping things the same because we perceive any change as a loss. This is especially true when it comes to removing toxic screens. We think that since our kids already have access, it is easier to keep them. It becomes too overwhelming to think about making the change.

Truth: Change is hard. Doing the right thing is hard. Implementing screen changes is one of the hardest decisions because it is one of the most deeply rooted habits in our culture today. The truth is that generally, anything worth doing is hard to do, and this is no exception. Many kids get hurt because parents aren’t willing to make the hard changes to break them of their screen dependencies.

Availability Bias: Out-of-context examples.

“I know a friend whose son was never allowed to drink alcohol before he went to college, so he binged and ended up with alcohol poisoning as a freshman.”

“I knew a girl who hated her mom for years because she was not allowed to have a smartphone.”

Truth: This mental shortcut relies on examples that come to mind when a certain subject is brought up. If we remember it quickly it must be more true. You think of a friend that experiences a similar situation and jump to the same conclusion without context. The fact that you remember a particular story when you are discussing a topic makes it feel important and true, but generally we don’t recall the whole story.

How to win the bias war

You beat the biases and blind spots when you can get solid information and then step back and look at the problem from a new perspective. The sooner you understand the science and warning signs, the less biased you will be.

For example, it’s never productive for kids to spend more time on leisure screens than they spend on life skills or time with people. We know that it is normal for kids to choose low-effort, high-reward activities over harder life skills and we also know that screens are too powerful for them to handle. That is why they need parents to objectively assess the risks and make proper parenting decisions.

And yet at the end of the day, parents don’t need research studies or social groups to confirm what they know deep down to be true for their child. The day you have a gut feeling that something is wrong is the day to take action.

Stop trying to find people to confirm the bias that screens and video games can be good for your kids. Get clear information, be willing to accept new information, and change what you are doing. If you find yourself searching for more support or excuses to keep your kids on their screens when there are signs of trouble, that is a red flag.

Remove the blind spots

The day I realized that my way of thinking about entertainment screens was completely misguided I was in the car driving my oldest son home from college. He said, “Mom, that video game did something to me, I have been in bed for a week, and I am depressed.” That was my defining moment. I was no longer interested in soothing my biases: I had to fight for him. I had to change my thinking for the sake of my son. It was lonely and hard at first, but I knew it had to be done.

Looking back, I regret that my blind spots were big and that I made many big mistakes. I know now that prevention is key. A good coach knows that an ounce of early detection and prevention is worth a pound of cure. Don’t wait another day to step outside your current biases. Stand up for your kids now and take action for your family.